The Best 15 Changes to Fencing in the Last 40 Years

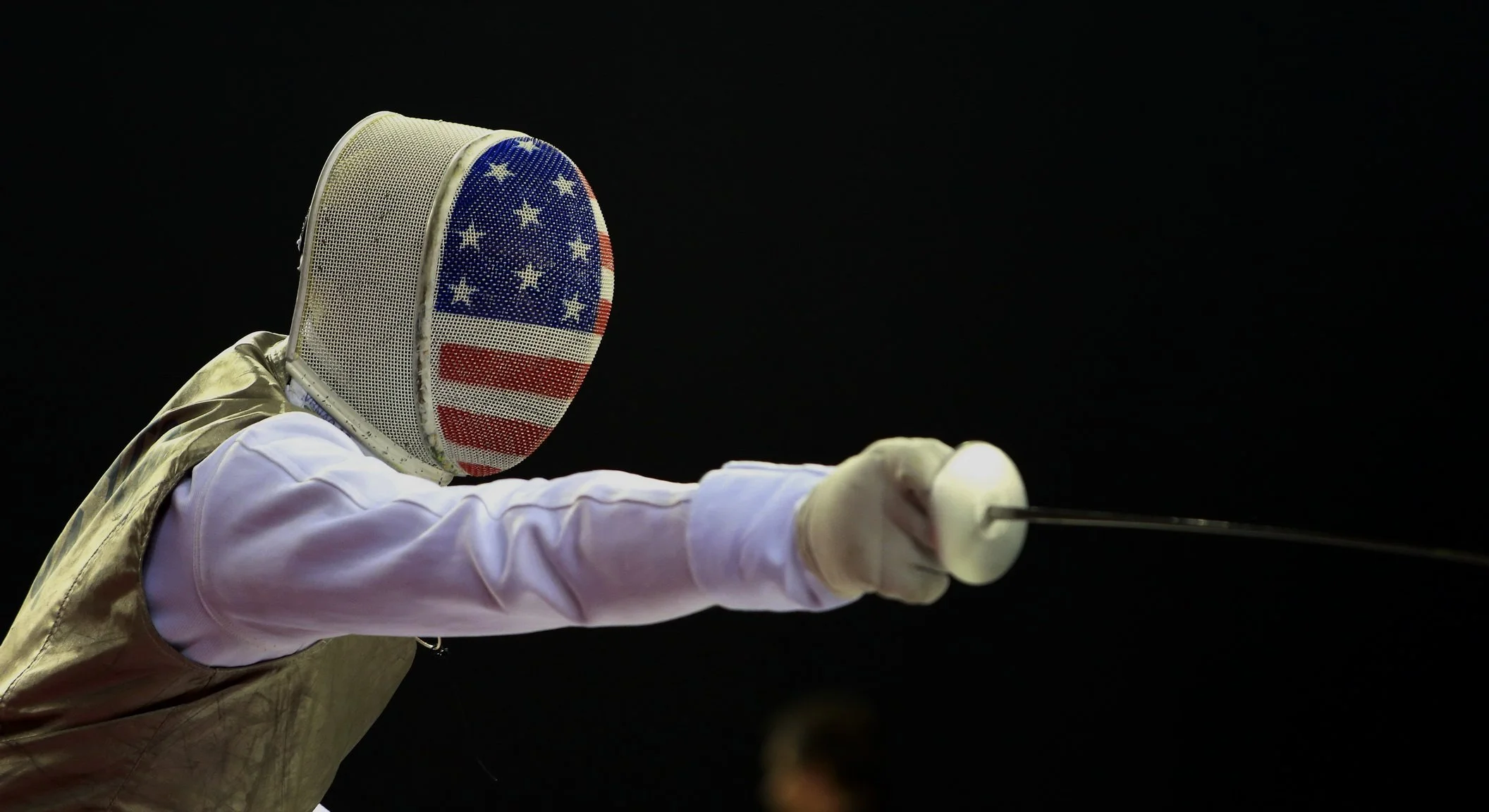

All photos by Serge Timacheff

Having been involved in fencing for over half a century (yikes!), including serving as a referee or team captain at four Olympics and 15 World Championships, and for eight years on the FIE Rules Commission, I’ve pretty much seen it all.

Fencing is an evolving sport in many ways, and has been since being one of the original Olympic events in 1896.

I’ve seen the good, the bad and the ugly when it comes to innovations and rules changes.

In this column, we will stay positive and look at the best changes to our sport over the last 40 years, at least in my opinion.

We will go in order of least to most significant, but each is notable and important.

15) (tie) Switching the Lights

Until about 20 years ago, the lights were reversed from where they are now. In other words, when Fencer A hit Fencer B, Fencer B’s light would go off.

It was quite the transition for long-time referees when they switched the lights. Now, of course, when Fencer A hits Fencer B, it is Fencer A’s light that goes off.

It just makes more sense for someone watching the sport.

15) (tie) Touches For vs. Touches Against

Referee hand signals were ridiculed when introduced.

I can’t think of any other sport that scores against. But fencing used to. This is one of those changes that made perfect sense and left you scratching your head as to why it was ever scored against.

14) The Hand Signals

I will never forget my introduction to the hand signals.

At the 1996 test event in Atlanta prior to the Olympics, the Olympic referees were brought in. Prior to the competition, we had the referees meeting with the FIE’s Arthur Cramer. Cramer was a former military officer in Brazil and often acted the part.

Over time, hand signals were regarded as a “great step forward” for fencing.

On this day, Cramer was on a mission to put the Olympic referees through hand-signal boot camp, as the hand signals were his innovation.

Oh, did we have a laugh. We laughed at the idea. We laughed at Cramer when he got up on a chair and demonstrated his newfangled hand signals. It was a regular yuck-fest. Candidly, we mocked Cramer and thought this was the most ridiculous thing ever.

But we were dead wrong. As it turned out, the invention of the hand signals was a great step forward for fencing. It enabled everyone in the venue, from fencers to coaches to spectators, to understand exactly what the referee was calling.

Apologies and kudos go out to Arthur Cramer.

13) Shortening the Length of a Pool Bout

Back in my day, the length of a pool bout was five minutes plus a one last minute if the score was tied for men, and four minutes plus a one last minute for women. However, if the score was tied at the end of the “last” minute, the bout continued until the next touch without any time limit! See #7 to see how this was corrected.

There was a “one-minute warning” given to the fencers after an action that caused a stoppage. Referees were mandated to say, “Approximately one minute left to fence.”

This was a lot of time to score five touches, and many bouts were snooze-fests.

The FIE shortened the bout to three minutes, which encouraged more action in a shorter timeframe.

12) Making Part of the Foil Bib Valid Target

It used to be so frustrating to fence someone whose bib, which was not valid target back in the day, basically cover half of their chest. My 1983 World Championships teammate Pat Gerard was a good guy, but when I fenced him all I saw was an arm, a foil and a bib covering his torso.

However, the bib became valid target area soon after the lengthening of the contact time in foil.

An unintended consequence of the contact time change was fencers started angling their heads forward and awkwardly jack-knifing their torsos. Fencers were mostly concerned about lessening the front target area, as the back became less vulnerable due to the flicks being mostly negated because of the longer contact time. Valid target area in foil was at a premium.

Nothing footwork-related can cause proper point-in-line priority to be lost.

The decision to make the lower part of the foil bib valid target was long overdue.

11) A Line is a Line is a Line

The point-in-line interpretation has changed over the years. At one point, it was so complicated and counterintuitive that referees couldn’t possibly be consistent in their calls.

There was a time about 20 years ago where Fencer A had a properly established point-in-line and Fencer B started an action against the line, obviously without the right-of-way. If Fencer A, still with the point-in-line properly established, then advanced, retreated, lunged or fleched against Fencer B’s counterattack, Fencer A’s action was now considered the counterattack.

As I said, this was confusing, complicated, counterintuitive and likely the worst interpretation of point-in-line in the sport’s history.

Thankfully, the current point-in-line interpretation is the best in the sport’s history. It is clean, simple, and, most of all, logical.

Once a fencer has properly established a point-in-line, nothing footwork-related can cause that line to be lost.

10) Posting of the Pool Results Prior to the DE Table Being Finalized

Posting pool results has long been a standard in international fencing.

I was the first alternate for the 1982 World Championship Team. While I can’t say for sure I would have made the team if not for a horrible seeding error of the DE table at the Nationals, I can say for sure I would have had different opponents.

In 1982, the NAC format had three or four rounds, with the last two counting as seeding rounds for the direct elimination table.

After my elimination in repechage, I was in the stands with my old friend Jim Powers. I asked him how he finished. He said 13th. Immediately, I knew something was very wrong. My final placing was 14th, yet I was seeded higher than Powers going into the DEs. This, of course, was impossible.

Sure enough, when I brought this to the attention of the bout committee, they acknowledged the egregious error had occurred and the table was improperly seeded.

Yes, this did happen, and I believe this incident led to the posting of the pool results becoming mandatory prior to seeding the DE table, at least at USA Fencing competitions.

9) Elimination of the Meter and Two-Meter Warnings

There used to be a meter warning in foil, and a two-meter warning in saber and epee.

Warning lines on the piste have evolved over the years.

A fencer would retreat with one foot off the end line. In foil, he’d be placed with the back foot on the one-meter line, a meter in front of the endline. In saber and epee, the back foot on the two-meter line, two meters in front of the endline.

Retreating off the end line with both feet would be a point for the opponent.

A fencer could regain the initial status, and not be at risk of losing a point by retreating off the end line, by advancing and touching the center line with even the tip of the front foot.

So, it became a game of cat-and-mouse, with fencers ceding ground easily and taking the meter warnings knowing they’d most likely regain the center line and be able to start over.

End-of-strip fencing can be dramatic and exciting, where rules and good refereeing become essential.

It was almost comical to see the fencer who already had the one- or two-meter warning inch the front toe over the center line and try to make sure the referee saw it, often pointing with their back hand at the toe to alert the referee.

During the men’s saber finals at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, held in a sold-out hall at the Long Beach Convention Center, two fencers were going back and forth and taking their two-meter warnings. Over and over, we would head public address announcer, say, “…two-meter warning.”

Finally, the exasperated announcer, instead of saying “two-meter warning” for the umpteenth time, says, “Yup, you guessed it.”

It was hilarious, but not to the FIE, as it made a mockery of saber fencing, let alone during the Olympic Games. As a result, the FIE made a huge improvement to the sport when they eliminated the meter and two-meter warnings.

8) Elimination of the Fleche/Crossover in Saber

The problem was not with the actual fleche. Rather, it was that fencers were just running up-and-down the strip. So, while the fleche and crossover are considered interchangeable, it was the perpetual crossover that was the culprit. Think of Fred Flintstone running in his car.

Flunges. Crossovers. Saber!

It was a mess. Lots of running, very few actions.

Once the fleche/crossover was made illegal, the saber fencers developed almost super-human footwork, as well as incorporating the spectacular fleche-like “flunge,” or flying lunge.

As a result, saber fencing has flourished and is more exciting than ever.

7) The Birth of Priority and the Sudden-Death Overtime Minute

Back in the 80s, there was no “final or overtime minute” if the score was tied. The bout could theoretically go on forever.

And one time it almost did. I was fencing Canada’s Luc Rocheleau in the finals of the 1981 Michel Alaux NAC at Hunter College in New York City. At the time, the DE bouts went to 10 touches, with a time limit of 9 minutes + 1 (not overtime, just the supposed final minute.)

At the end of the 10 minutes, the score was tied at 1-1. We were two fencers who relied on defense and were steadfast to win or lose in that manner. The bout continued for another 30 minutes without a touch, as neither wanted to blink and, heaven forbid, take a risk and attack. I finally did and the dreadful bout mercifully ended.

Hard to believe, but that NAC ended at 2:10 AM.

The incorporation of the overtime minute, for pool and DE bouts, replete with the coin flip/random draw to determine priority if no touches were scored in the final minute, guaranteed all bouts would have a finite end time.

6) The Domestic Competition Format

Candidly, the NACs were outright endurance contests and regularly ended after midnight.

The first round would usually have two flights. Unbelievably and incomprehensible, in the early years of the NACs the best fencer/referee from the second flight would be required to officiate the first flight, as not enough referees were hired. I’m not making this up. I speak from experience, as I’d be refereeing a pool of seven for two hours before I’d have to fence my first-round pool!

In most cases, there would be four rounds of pools, with the last two counting for seeding into a DE table of 32, with repechage.

Now, we have one round of pools (with the exception of Division I foil and epee events with 203 fencers or more, which have two rounds of pools) and DEs straight to the finish.

Nice and neat and tidy…and timely.

5) The Birth of the North American Cup (NAC)

The North American Circuit (now called a North American “Cup”), or NAC, was first implemented during the 1979-80 season.

NACs, then and now — no more repechage, but big events and lots of fencing to manage in a day.

Prior to the NACs, which allowed any fencer to enter these national-point competitions, there was a restrictive and unfair system that arbitrarily limited the top 24 fencers in each weapon to compete in closed-point competitions twice a year.

The only “open” national event where fencers could earn points was the Nationals, although it wasn’t really open as fencers had to qualify through their division or section.

Unfortunately for me, I was on the wrong side of this closed system. At my first Nationals in 1978, we still had the pool system right through the finals. In the quarters, I went 2-3 and was eliminated. As brutally bad luck would have it, I was tied for the 24th and final spot (based on the results of the Nationals and the previous season’s rolling points) and finished 25th by two indicators.

As a result of another fencer having two fewer touches against (at the time it was touches against that was the tiebreaker) in a different pool, I was completely shut-out of the two closed-point competitions during the 1978-79 season.

This system was severely flawed and served to deprive many up-and-coming fencers of a chance to climb the ladder.

Considering the awful system it replaced, the birth of the North American Cup was one of the greatest steps forward for American fencing.

4) The International Competition Format

The FIE format has evolved in a similar manner to the domestic format.

Back in the 70s, there were pools of six right until a final pool of six. This led to all sorts of collusion. As an example, Fencer A would be 4-0 going into his last bout against Fencer B, who was 2-2. Fencer A was already qualified into the next round, as three fencers were promoted, while Fencer B had to win the last bout to go 3-2 to have a chance to reach the next round.

“…in the hallway or catacombs, a deal would be struck between the fencers…”

So, in the hallway or catacombs, a deal would be struck between the fencers, often through their coaches. The deal could include a monetary payment, but part of the deal was that Fencer B, the recipient of the thrown bout in the current pool, would have to return the favor in the subsequent round or whenever Fencer A called-in the marker.

Just for the record, this happened on a regular basis during the pools-only era. Bout-throwing was a matter-of-fact part of competitions.

In 1972, I was just 15 but came to the Munich Olympics with my father Dan, who was a referee. I watched in horror as American Paul Apostol, already finished at 3-2 in his semifinal saber pool, was deprived of a spot in the Olympic finals due to blatant collusion.

In the last bout of the pool, the aforementioned situation arose where Fencer A, sure enough, was 4-0 and into the finals, was fencing Fencer B, who was 2-2. Now, there was an additional wrinkle. Not only did Fencer B have to win to go 3-2, but he needed to win by a score of 5-1 in order to qualify over Apostol on indicators.

The final score, of course, was 5-1. The total cost for the thrown bout that cost Paul Apostol a rightful place in the 1972 Olympic saber finals? $50, which was verified by Team USA leadership after the fact (or should I say fiction?).

Now, with a single round of pools and then direct elimination, collusion is mostly a thing of the dark past.

3) The Team Relay

When I first qualified for the New York Fencers Club foil team in 1981, there were teams of three fencers that would fence the opposing team’s three fencers. This was clean, as one team had to win based on bouts won (5-4, for instance).

Four-person teams, which include an alternate, have an inherent advantage.

Then, the format changed to teams of four. This created a problem, as the final score could have been 8-8. In that case, you went to indicators. I still feel the pain of the 1987 Pan American Games in Indianapolis, as the U.S. foil team lost 8-8, on touches, to Canada in the semifinal.

Can you imagine a tied baseball game being decided on which team had more hits? Or a tied hockey game being decided on which team had more shots on goal? Or a tied football game being decided by which team had more rushing yards? Of course not. But in fencing, a differential of one touch in 16 bouts, with the bout score tied 8-8, determined the winner. Ridiculous.

The only benefit of the four-person team compared with the three-person team was the stronger and deeper team rightfully had an advantage.

Eventually, the relay was born. Ironically, one of the main reasons for the relay to give a puncher’s chance to a team with one superstar, which had the effect of disadvantaging the stronger and deeper team. The team relay, as we all know, has become possibly the most exciting event in our sport.

The relay format is undeniably great for fencing, as it provides for some “must-see TV,” while giving underdogs a chance to upset the strongest teams. However, many old schoolers argue that the relay format makes a mockery of the “team” concept by potentially giving too much weight to one fencer while at the same time negating the depth of the best teams.

That is a valid point-of-view, but the relay still was one of the best changes for our sport.

1) (tie) Electrification of Saber

Until the 1988 Olympics, saber was fenced dry. You had a referee and four side judges. As someone who officiated dry saber at the World Championships in 1986, I can assure you it was extremely subjective.

Saber’s evolution from dry to electrical scoring, and even electrical wireless. Still subjective, but a lot less chaos and hysteria.

Not only did you have to worry about a referee getting the call right, you also had to contend with side judges seeing if the fencer hit or not. And, when you threw in the politics involved, it was really a circus. The referee had one and a half votes, and the side judges one each. If both side judges voted the same, the referee’s vote was moot. If one side judge abstained, the referee’s vote would rule over the other judge’s vote, if they voted differently.

With the birth of electric saber, the subjectivity of whether a touch actually hit was eliminated, the imperfect and sometimes agenda-driven side judges were eliminated, and the referee was solely tasked with determining the right-of-way.

Of course, it wasn’t perfect, as the lack of off-target lights for hits not on the electric lame leads to actions without the right-of-way scoring.

While saber refereeing is still subjective due to the lightness and speed of the weapon combined with the incredible footwork of the fencers, the chaos and hysteria we saw in dry saber on nearly every touch is a thing of the past.

1) (tie) Video Replay

The utilization of video replay is the great equalizer. It caused mediocre referees to become good, good referees to become very good, and great referees to become nearly perfect. It’s basically the safety net for mistakes.

Video replay is responsible for the single-biggest improvement to the competitive environment.

Video replay is responsible for the single-biggest improvement to the competitive environment. That is perfectly illustrated by the exponentially improved atmosphere at what I consider to be the most tense and exciting competition, the Ivy League Championships.

At the “Ivies,” there would be visceral reactions to calls on a regular basis. I’ve been on the floor at four Olympics, but the level of intensity at the Ivies was at a completely different level.

The Ivies have maintained its atypically supercharged atmosphere since the incorporation of video replay a few years back. But the focus changed dramatically, with more cheering for touches as opposed to jeering at referees’ calls.

Fencing is a results-oriented business, and the most important aspect of fencing is to get the calls right for the fencers. In addition to calming-downing the atmosphere, video replay has done just that.

I’d like to relate a “Tale of Two Olympics” story, which, to paraphrase the old Wide World of Sports opening, saw “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.” The lack of replay helped cause that agony, while the inclusion of replay was responsible for the thrill.

Keeth Smart and a solemn moment at the 2004 Athens Olympic Games.

At the 2004 Athens Olympics, the men’s saber team lost to France in the semifinals 45-44. At 44-44, there were three nearly identical actions in the box by Keeth Smart and Damien Touya. The referee called simultaneous on the first two and incomprehensibly split the baby on the third and gave it Touya.

Had we had video replay in Athens, I believe the United States might have had another medal.

Fast-forward to the 2008 Beijing Olympics where video replay, combined with Smart’s heroics, actually led to the silver medal. At 43-44, match point to get into the finals, Smart veered off the strip while pushing Russia’s Stanislav Podzniakov. The side judge, who was directly in Smart’s view at the end of the strip, raised his hand to indicate Smart was off the strip. Smart saw this and immediately let his guard down, literally and figuratively. Naturally, Podzniakov hit the defenseless Smart, while at the same time the side judge pulled down his raised arm. He evidently panicked. I believe the only people in the venue who saw the side judge’s action were the members of our team, as our team box was facing him directly.

It all happened in a blink.

Keeth Smart and teammates with an emotional celebration in Beijing.

From the box, I told Keeth not to shake hands and yelled to the late Hungarian referee Zsolt Kaposvari that we wanted a video review. Kaposvari never saw the side judge’s hand go up, and the review did not show it. Fortunately, the review clearly showed Smart going off the lateral boundary with both feet, which negated any subsequent action from him or the opponent.

Unbelievably, the match-ending touch was annulled, and we got an Olympic do-over! Smart miraculously scored the next two touches, and we were into the gold medal match!

The eventual silver medal would never have been won if not for video replay.

Without a question, the electrification of saber and inclusion of video replay are the two most impactful changes to fencing over the last 40 years.

__________________________________________________________________________________

That was quite a list and a trip down memory lane.

But there are two more changes that supersede all others and deserve their own lofty category.

2023 Daytona Veteran Fencing World Championships: Demonstrating the lifelong qualities of our sport.

2) Birth of the Veteran World Championships

Fencing has always been touted as a lifetime sport. I saw my dad fence into his 70s. But from a competitive standpoint, the seasoned citizens didn’t have their age category events.

With the birth of the Veteran World Championships in 1997, fencing really became a lifetime sport.

Having recently served as FIE commentator at the Vet Worlds in Daytona Beach, I saw firsthand fencers from 50 to 80 competing with unmatched joie de vivre.

The Vet Worlds provide an avenue for fencers who still love competing at a high level to compete on equal footing within their age categories.

Lifetime sport, indeed!

1) Inclusion of Women’s Epee and Saber at the World Championships and Olympic Games

An exuberant Mariel Zagunis and Sada Jacobson with their medals at the 2004 Athens Olympic Games.

Everything else previously mentioned in this column pales in comparison to women gaining equality in the world of fencing.

The FIE first held the World Championships in 1921. From its inception until 1988, the only women’s events were in foil.

In 1988, the FIE added the women’s epee individual and team events to its World Championships program. It took eight years and two Olympic cycles, but women’s epee was finally added by the IOC to the Olympic program in Atlanta in 1996.

The FIE added women’s saber to the World Championships in 1999, and the IOC finally added women’s saber to the Olympic program for the 2004 Games in Athens.

Jeff Bukantz doing commentary at the Daytona Vet Worlds

For those too young to know, in Athens the United States won its first Olympic medals since Peter Westbrook’s bronze at the 1984 Los Angeles Games 20 years earlier, when Mariel Zagunis won the gold and Sada Jacobson won the bronze.

And those two medals were just rewards for USA Fencing, as it led the charge for the inclusion of women’s saber into the 2004 Olympic program. That effort was spearheaded by then-president Stacey Johnson, along with USA FIE Commission members Carl Borack and the late Sam Cheris.